Joseph Beuys described art as a means of escaping a process of “boring, naturalistic repetition of what is already done by nature.” Unconstrained in its output, art has the freedom to be truly innovative. Is this a good thing? Below, I explore three exhibitions happening in London this month that present possible answers to this question. From the industrial revolution to the advent of the internet to recent developments in artificial intelligence, these shows remind us of the growing pains that come alongside human innovation.

GRAY WIELEBINSKI, OIL AND WATER, HALES GALLERY

JUNE 25TH - JULY 31ST

Installation view: Gray Wielebinski, Oil and Water. Courtesy of Hales Gallery and the artist.

When combined in the same vessel, water and oil naturally separate. The two substances’ relative densities cause the oil to sink to the bottom and the water to rise to the top. But the title of Gray Wielebinski’s first solo exhibition with Hales Gallery has more to do with the artist’s personal geography than chemistry. It references Dallas and Los Angeles, two cities where they spent their formative years and of which oil mining and water syphoning industries form the respective foundations. In both of these places, human life and the natural world have an uneasy relationship. Like water on oil, the trappings of civiliation sit uncomfortably atop the natural world, unable to form a cohesive emulsion. Pumpjacks in Texas and aqueducts in California are an unnatural part of the landscape, extracting resources from the planet on an industrial scale.

This uncomfortable relationship is referenced in the motif of the horse repeated throughout this exhibition. A normally majestic, beautiful and unconstrained creature, Wielebinski’s horses bring an uncanny feeling of forced order. In their sculptures they are cold and angular, cast in metal. They look more like pieces of industrial equipment than friendly equestrian companions. In their ink drawings they are dressed in elaborate costumes, looking out suspiciously. In both cases, we see a friction between man and nature defined by our desire to dominate, control and extract value.

This friction is an inescapable part of the artist’s identity. As they put it, ‘both cities made me, but they were both made by a type of “original sin” that continues to live on physically, psychically, and aesthetically throughout the cities themselves at almost every level of daily life.’

IRL (IN REAL LIFE), TIMOTHY TAYLOR

JULY 8TH - AUGUST 21ST

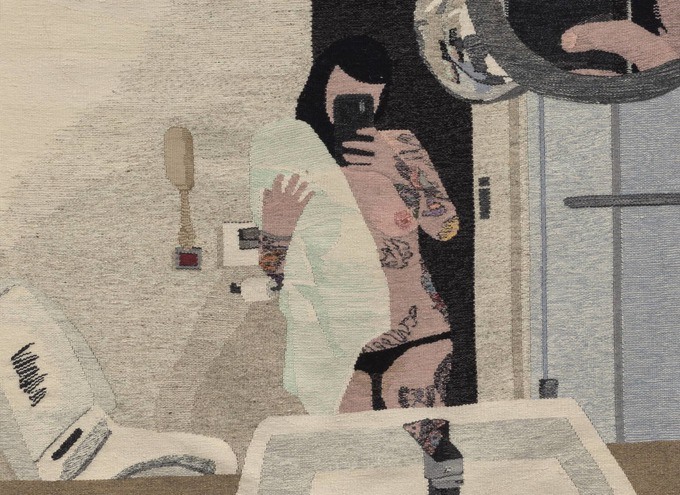

Installation view: IRL (In Real Life). Courtesy of Timothy Taylor.

Where else? There was presumably a time where the phrase 'IRL' – at least when applied to 'real' things – was meaningless, because there was nowhere else for these things to exist. Now there is a clear distinction between the online and offline worlds and things that don’t exist IRL can be just as real as those that do.

The events of the last year have catalysed a sudden acceleration and widening of conversations about the relative merits of online and offline spaces as hosts for many forms of intercourse or connection, including experiencing art. I have found myself tempted to tune out of these conversations, denigrating them with the assumption that they are a product of the time and of little transhistorical importance. But really, I don’t think this is the case. They were happening before COVID and I don’t doubt that they will continue for a long time after. In 2019, the Museum der bildenden Künste Leipzig mounted a huge group exhibition entitled Link in Bio, enquiring into “how the production and reception of art are changing in the age of social media.”

Timothy Taylor’s Summer Group Show follows a similar line of enquiry. The peaks and valleys on the surfaces of Kesewa Aboah’s creased textile works create an effect of light and dark, highlights and shadows. Erin M. Riley’s tapestries seem almost pixelated, the image-making process naturally limited by the loom she weaves them on. These artists, two of the twelve on show, have an intimate relationship with materiality and tactility. They are unmistakably physical – made to be experienced IRL. Many of the artists go beyond the remit of Link in Bio, looking at the online/offline gulf with reference to more general ideas of the social and sensory experience. Honor Titus and Antonia Showering, for example, paint hazy recollections of tender and intimate moments shared between their subjects.

AI PORTRAITURE: US AND THEM, ANNKA KULTYS

JUNE 24TH - JULY 24TH

Exhibition image courtesy of Annka Kultys

“Will the machine cut out the creative artists? I sincerely hope, that machines will never replace the creative artist, but in good conscience I cannot say that they never could.” This was written in 1960 by electrical engineer and physicist Dennis Gabor. At the time, I don’t imagine that Gabor and his readers had a clear idea of how this hypothetical robot-artist might function within the art world. Over 60 years later, we don’t need to imagine.

Ai-Da, one of the artists in this exhibition, has a short but impressive CV including exhibitions at The Barbican, Tate Modern and König Galerie. Her original oil paintings and sculptures can be purchased from Annka Kultys and she has delivered a handful of talks about her work and the ideas surrounding it. It’s also worth mentioning that she is a life-sized humanoid robot.

“The intersection between art and technology” is an expression I tend to switch off when I hear. Like 'liminal space' or 'anthropocene' it has been wheeled out by artists, dealers and writers to the point where the words have lost most of their meaning. It could also be seen as something of a non sequitur. The idea of an intersection between these two things assumes that they are essentially separate entities. For many of the artists in this exhibition, Ai-Da included, art is technology and vice versa.

From Andy Warhol picking up a video camera in the 1960s to scores of NFT-pushers in the last year, artists using new technology as a novel addition to their practice – as a means to an end – is not new. What is new, what Dennis Gabor feared and what this exhibition brings to the fore is a type of art that sidesteps human artists and traditional media entirely, in favour of producing work made by and/or of artificial intelligence.

Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol Sandra Blow

Sandra Blow Tabitha Soren

Tabitha Soren Patrick Hughes

Patrick Hughes Day Bowman

Day Bowman Nelson Makamo

Nelson Makamo Takashi Murakami

Takashi Murakami Daisy Cook

Daisy Cook Fred Ingrams

Fred Ingrams Barbara Rae

Barbara Rae Bruce Mclean

Bruce Mclean Tracey Emin

Tracey Emin