Art is neither responsible for the reporting of facts nor the creation of fictions. In the gallery space, artists and curators are free to reflect realities or manufacture fantasies as they wish. Whether true, false or somewhere in between, many of the most compelling exhibitions are those that tell stories.

Below are four such exhibitions on show in London this month. Their stories can be, as in the cases of Kenturah Davis and William MacKinnon, symbolised in artworks’ formal features. In Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s work, the stories contain blanks to be filled in by the viewer. Others, like Agnes Martin and Jule Korneffel, write stories without words, instead using the subtle language of abstraction.

Lines of Thought, Pippy Houldsworth Gallery

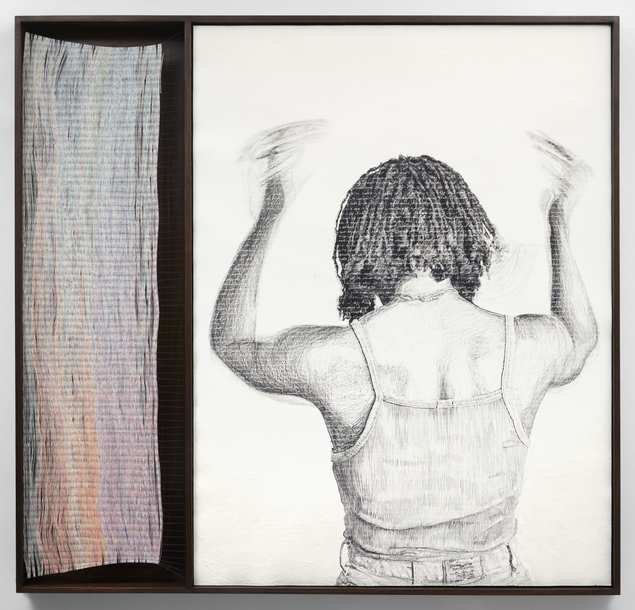

Kenturah Davies, Limen III - courtesy of Pippy Houldsworth Gallery and the artist

As concepts, the written word and the grid seem to work against each other. The former is a mode of unconstrained expression and the latter a constraining force. This three-person show explores how the two apparently disparate themes come together to create impactful and deeply personal messages.

Agnes Martin’s work is a clear and recognizable example of this. Her meticulously drawn grids create a delicate visual field wherein the smallest deviation from the norm becomes a communication as explicit and emotional as normal prose can be. Kenturah Davis’ Limen series also utilises grid-like structures to communicate emotional truths. Her process begins with hand-writing pages of her reflections on subjects ranging from black holes and time travel to philosophy and critical theory. She then turns these pages into textiles, entrenching the freedom of her writing in the regimented process of weaving.Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Fly in League With The Night, Tate Britain

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, A Passion Like No Other - courtesy of Lonti Ebers and the artist

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s CV reads like a gazetteer of well respected galleries, museums and collections across the world. The artist’s mid-career survey exhibition at the Tate Britain is her latest stop on this tour.

Her characters are imagined, and she makes a specific effort to divorce them from a specific time and place. The space behind and around the subject is often obscured to the point where it becomes an abstract colour-field, limited only to features that can be used as props for the focus of the images: the people. By abstracting from real-world subjects and scenarios, the artist creates paintings with relatability and pertinence that varies from viewer to viewer, allowing room for each to give their own subjective meaning to her work.

Jule Korneffel, All That Kale, Claas Reiss

Jule Korneffel, A Sun - courtesy of Claas Reiss and the artist

Claas Reiss is a brand new and mysterious gallery, located just off Regents Park - a short walk to the north of the art hubs of Mayfair, Fitzrovia and Soho. Its website does not list a roster of artists, nor does it give anything away about what we can expect from its programming beyond this exhibition. Its Instagram page, rich with painterly artworks that generally sit somewhere in the middle of the abstract-figurative spectrum, seems to be the best window into its eponymous director and founder’s tastes. Having been active for over two years before the gallery’s inaugural show opening this month, it features established members of the contemporary canon such as Alice Neel and Marlene Dumas to hotly-tipped emerging artists like Emma Fineman and Rhiannon Salisbury.

The maiden exhibition is billed to show six new paintings from German abstract painter Jule Korneffel. Her reductive canvases are home to sparse groups of floating forms, the isolation of which the artist relates to her own experience living in New York during the coronavirus pandemic.

William MacKinnon, Strive for the Light, Simon Lee Gallery

William MacKinnon, The Legacy Large Family - courtesy of Simon Lee Gallery and the artist

What is a landscape? The word brings to mind an expanse, punctuated by natural or manmade objects and cut off by the sky above it. However, we also hear about political and cultural landscapes, which don’t seem to share any of these features. Ultimately, a landscape is a space; a backdrop against which things can exist and events can happen.

William MacKinnon is well acquainted with the baron landscapes of his Australian home, and paints them masterfully: the stillness, the red river gum trees, the dusty horizons. However the works on show here, the artist’s first UK solo exhibition, do not just document the immediate physical facts of the landscape. They are also rife with oblique references to its personal and cultural histories.

Trees are ever-present in the paintings, becoming symbolic of the range of emotions present in MacKinnon’s “psychological histories”. In some works, they provide shelter and respite from the sun. In others, tangled branches compete for light and water. In Uprooted, which stands at an impressive 260cm tall, we see a single tree laying horizontally having yielded to the pervasive force of the wind.